John Ruskin released each of the three volumes of The Stones of Venice over a two-year period from 1851 to 1853. The first volume, “The Foundations,” is an architectural treatise that specifies the rules of architecture. For this reason it has been compared with Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria of 1452 because both treatises approach architecture as a combination of both construction and decoration. With the exception of the first chapter, “The Quarry,” this volume deals very little with the actual city of Venice, but rather continues Ruskin’s work in The Seven Lamps of Architecture by analyzing specific architectural details and concluding whether or not they are in accordance with the principles laid out in his previous work.

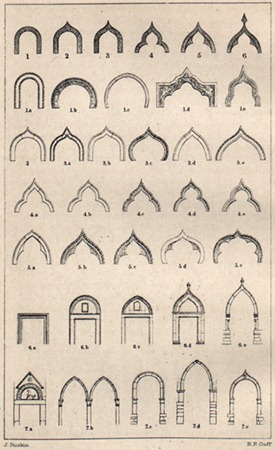

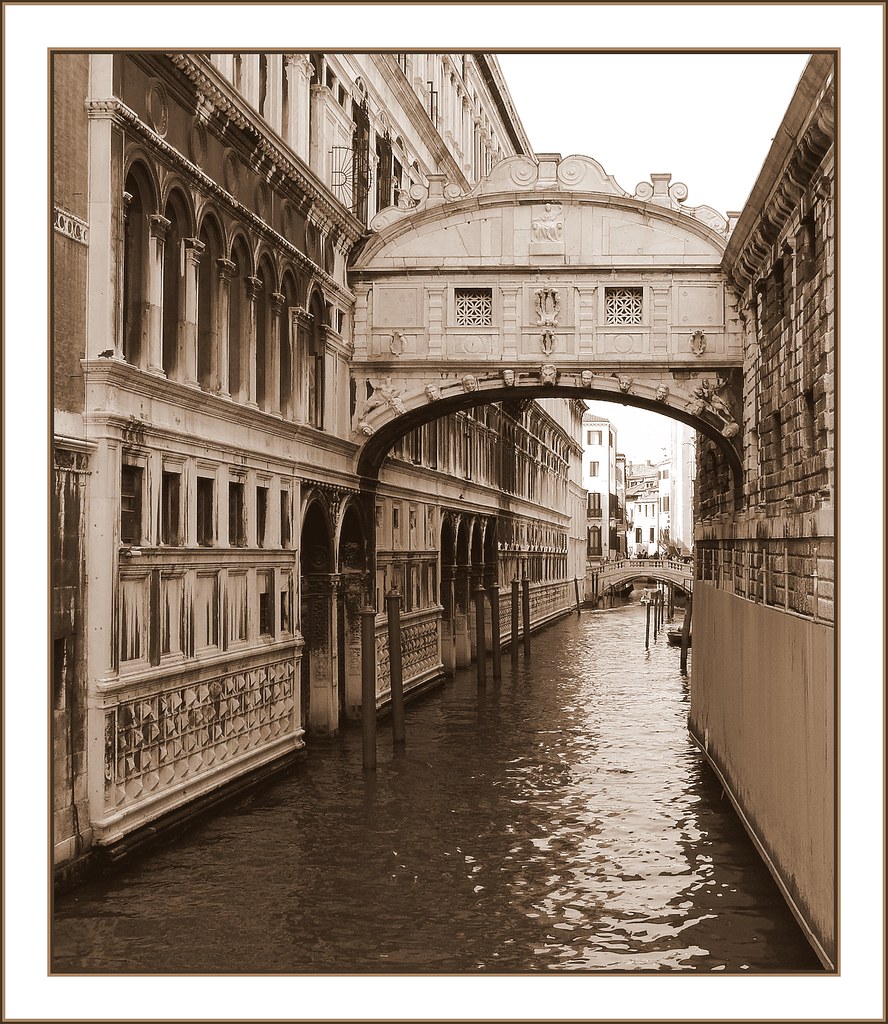

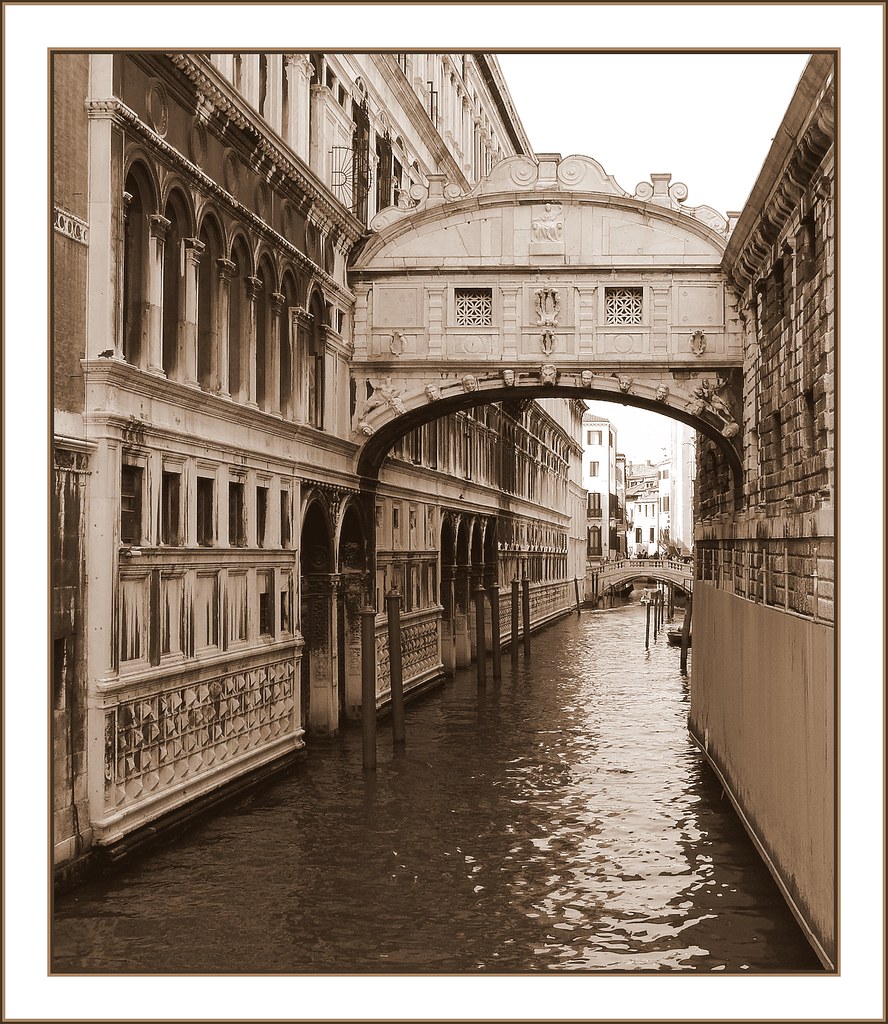

In contrast to the first volume of The Stones of Venice, the second and third volumes deal with specific structures in the city of Venice. The second volume is subtitled “The Sea Stories,” a reference to the lowest story of a Venetian building, called the sea story. This volume looks specifically at Byzantine and Gothic architecture within the city, while clearly privileging these styles above the Venetian Renaissance that he discusses in the third volume, “The Fall.” Throughout each volume, Ruskin discusses both specific buildings, such as St. Mark’s and the Ducal Palace, and the stylistic evolution of numerous architectural features, including column bases, capitals, cornices, windows, and, most notably, arches. His studies of arches provide not only an example of the types of arches found around Venice, but also a “scheme for the development of the mature Gothic style,” as his chronology of stylistic progression focused mainly on this period.

Ruskin first begins his analysis of arches in “The Foundations” with three chapters devoted to his discussion of both the technical aspects of constructing an arch and a brief overview of the basic styles of arches throughout Italy and the rest of Europe. Here, beyond simply describing the arch as a functional element necessary for the support of a building, he gives the arch a moral element by creating a metaphor between an arch and man’s character.

The arch line, or curved shape of the arch, serves as its moral character, with the forces of gravity and weight from above being temptations for the arch to stray from its intended function. To protect the arch from these temptations, the voussoirs, or the particular stones of the arch, act as its protection against ruin. The connection between man and arch is as follows: “if either arch or man expose themselves to their special temptations or adverse forces, outside of the voussoirs or proper and appointed armor, both will fall.” By personifying the arch in this manner, Ruskin shows the reader a specific instance in which architecture serves as a moral force within Venice, or any other city. Once he informs the reader of the importance of a morally sound arch, he then describes the techniques required to construct such an arch, focusing mainly on the placement of masonry and proper distribution of weight above the arch. Throughout, he consistently privileges the Venetian Gothic over other forms of arches, praising its simple construction and exceptional weight distribution, and eventually concluding that “nothing can possibly be better or more graceful” than a well-constructed Venetian Gothic arch. He further expands on his love for this style in “The Sea Stories,” providing a thorough survey of the arch’s evolution over time.

Ziad A. Alameddine, Parts of An Arch

In this volume, Ruskin describes the development of Byzantine architecture, followed by the shift to the Gothic style and its subsequent development, focusing on the stylistic changes that took place in arches and other architectural elements as demonstrated on Venetian buildings. He chooses to focus on the arches of windows and doorways as evidence for his argument because he considers them the “most distinctly traceable” elements of a building. Interestingly, he points out that the Gothic reached Venice after it was already established on the mainland, meaning that Venice embraced the Byzantine far longer than other places in Italy. According to Ruskin, this signifies that the emergence of the Gothic in Venice was not a matter of architectural innovation, but rather a struggle between earlier conventions and a more contemporary style, equating early Gothic structures in the city to a prisoner “entangled among the enemy’s forces, and maintaining their ground till their friends came up to sustain them.” He illustrates this idea by chronicling the gradual changes to arches that occurred early in the shift towards the Gothic during the twelfth century, followed by later, more radical changes in the fifteenth century.

John Ruskin, The Orders of Venetian Arches, 1853, Vol. 2 of The Stones of Venice

Ruskin’s diagram, The Orders of Venetian Arches, exemplifies each of these changes that occurred. The diagram shows the six orders of Venetian windows that he developed, with the two bottom rows being successive styles of arched doorways. The first group shows a typical Byzantine arch, as can be seen at Palazzo Loredan and its neighbor Palazzo Farsetti, two early thirteenth century palaces located on the Grand Canal. A first order arch consists of a plain rounded arch, similar to Roman arches from antiquity.

Unknown architects, Palazzo Loredan (left) and Palazzo Farsetti (right), early thirteenth century, Grand Canal, Venice.

The second order has a point on the extrados, or outer edge, of the arch, with the intrados, or inner edge, still rounded. This order can be seen on the second story windows of another early thirteenth century structure on the Grand Canal, the Ca’ da Mosto.

Unknown architect, Ca‘ da Mosto, early thirteenth century, Grand Canal, Venice

Moving into the third order, both the extrados and intrados are pointed, like in the early fifteenth century window arches at Palazzo Zorzi-Bon at San Severo.

Unknown architect, Palazzo Zorzi-Bon at San Severo, early fifteenth century, Venice

While the second and third orders represent the transitional styles moving towards the full Gothic, the fourth and fifth are purely Gothic, as well as the styles that lasted the longest, beginning in the thirteenth century and ending in the fifteenth. The fourth order is pointed like the third, but instead of straight moldings, they have a trefoil-like shape. The fifth order is similar, but has a straight molding with the trefoil shape placed inside of the arch. Both these orders can be seen on the main rows of windows on the Ca d’Oro, a palace designed by Giovanni and Bartolomeo Bon between 1428 and 1430. The windows of the lower arcade are of the fourth order, while those of the upper arcade are of the fifth.

Giovanni and Bartolomeo Bon, Ca d’Oro, 1428-1430, Grand Canal, Venice

As expected, Ruskin considers the fourth and fifth orders, those most Gothic in nature, to be the best, as “the root of all that is greatest in Christian art is struck in the thirteenth century.” Ruskin’s sixth and final order represents the late Gothic arch, present before architecture began to shift towards the Renaissance style. This order is basically the same as the fifth order, except with the addition of a finial above the point of the arch, as seen in Ruskin’s 1851 drawing Decoration by Disks: Palazzo dei Badoari Partecipazzi, found in the first volume of The Stones of Venice.

John Ruskin, Decoration by Disks: Palazzo dei Badoari Partecipazzi, 1851, Vol. 1 of The Stones of Venice

Though he presents these orders as if they succeed each other in neat, chronological fashion, this is certainly not the case. Each order overlaps with the others and several orders may exist on the same façade, as seen in the examples discussed here. Still, Ruskin’s classification provides a wonderful summation of the trajectory that Gothic architecture was following prior to its shift into the Renaissance.

By “The Fall,” the third volume of The Stones of Venice, Ruskin has little to say about the specifics of arches in architecture. This is likely because arches no longer possessed the variety they had during the Gothic period. Arches were generally plain Byzantine or Roman-style arches, the other five orders having fallen out of style. Still, he devotes this entire volume of The Stones of Venice to his discussion of Renaissance architecture, much of which is marked by a general distaste for the period as a whole. This is not to say that he disliked every Renaissance structure in Venice, for he greatly praise several of them, but he did feel that the era’s architecture grew progressively worse through each of the three stages within the Renaissance that he identified. The first stage, the Early Renaissance, was the “first corruptions introduced to the Gothic schools,” including the incorporation of precise symmetry, plain, undecorated stone, and a general feeling of academic coldness. However, he did praise this stage for its return to the earlier Byzantine elements of design and color, as seen in late fifteenth century buildings like the Palazzo Manzoni and the Scuola di San Marco.

Unknown architect, Palazzo Manzoni, late fifteenth century, Grand Canal, Venice

Pietro Lombardo and Mauro Codussi, Scuola di San Marco, 1495, Venice

However, by the time of the Roman Renaissance, the second stage, he saw that architecture had returned to the conventions of ancient Rome, but with none of its original vitality or innovation. Though he greatly praises the Palazzo Grimani, a 1575 structure by Michele Sanmicheli, for its delicate decoration and the majesty that it imparts to the Rialto, even calling it one of the greatest Renaissance palaces in Europe, his general sentiment about this period is that it is dull and unimaginative, regardless of its so-called perfection.

Michele Sanmicheli, Palazzo Grimani, 1575, Grand Canal, Venice

He completely omits any mention of Jacopo Sansovino’s Loggetta from this book and he describes Palladio, at the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, as having “pierced his pediment with a circular cavity, merely because he had not wit enough to fill it with sculpture.” Ruskin best sums up his feelings about the Roman Renaissance when he says, “It revisits the places through which it had passed in the morning light, but it is now with wearied limbs and under the gloomy shadows of evening,” suggesting that architecture that was once vibrant and imaginative has now been made tired and unoriginal.

Andrea Palladio, Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, begun in 1566, Venice

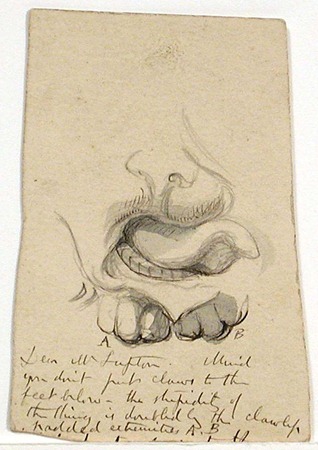

If Ruskin seems unimpressed with Early and High Renaissance styles, he is thoroughly disgusted by the third stage, “The Grotesque Renaissance,” his term for what is today know as the Baroque. Here, he feels architecture has lost all of the moral character he had described so eloquently in his earlier discussions on arches, and has instead been turned into the “perpetuation in stone of the ribaldries of drunkenness” and self-indulgence. This stage receives its name from the incorporation of grotesque elements, or distorted and ugly faces and bodies, often with protruding tongues, displayed on buildings and bridges. Ruskin makes a point to distinguish this “false grotesque” from the previous “true” version seen in the Gothic period, with the use of gargoyles and other distorted figures. He illustrates each of these versions in his drawing “Noble and Ignoble Grotesque,” found in the third volume of The Stones of Venice. In contrast to the earlier type, ignoble grotesque is an example of human imagination run amuck, as it steps out of the bounds of stable, organized renderings into images of the basest forms of debauchery and instability.

John Ruskin, Noble and Ignoble Grotesque, 1853, Vol. 3 of The Stones of Venice

In “The Grotesque Renaissance,“ The Church of Santa Maria Formosa receives the brunt of Ruskin’s scorn. The church was originally built in 1492 by Mauro Codussi, but one of its facades was redone by an unknown architect in 1604 in the Baroque style. It was the location of numerous grotesque elements, as well as being completely barren of any form of legitimate religious decoration, in Ruskin’s opinion.

Mauro Codusssi and unknown architect, Church of Santa Maria Formosa, church in 1492, facade in 1604, Venice

The worst feature of the church, according to Ruskin, is one of the heads, “leering in bestial degradation,” from the façade of the church. As offensive as he finds this head, he feels it is appropriate for this period because it serves as an incarnation of the degradation that resulted in the city’s decline, thereby allowing the viewer to “know what pestilence it was that came and breathed upon her beauty.”

Unknown sculptor, Head at Santa Maria Formosa, 1604, Venice

While Ruskin discusses numerous buildings that exemplify each of the three major styles in Venice, Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance, his discussion of the Ducal Palace is particularly interesting because it was built over several centuries and incorporates elements of each of the three styles. Ruskin uses the Ducal Palace as not only an example of each of the styles he had discussed, but also as an allegory to the history of the city itself. An 1852 letter to his father reads, “The whole book will be a kind of ‘moral of the Ducal Palace of Venice…’ I shall give a scattered description of a moulding here and an arch there- but they will all be mere notes to the account of the rise and fall of Venice.” Clearly, Ruskin did more than simply give a description of “a moulding here and an arch there” prior to his study of the Palace, but throughout the first and second volume, he repeatedly mentions its architectural integrity and slowly works his way up to his full analysis of the structure in the final chapter of “The Sea Stories.”

Filippo Calendario and Pietro Basejo, Sea Facade of Ducal Palace, 1361, Venice

The Ducal Palace, “the central building of the world,” was rebuilt by a variety of architects during each of the three periods that Ruskin discusses. Unfortunately, the Byzantine palace was almost entirely destroyed and built over when the Gothic palace was constructed. While some of the Gothic palace was built over, much of it now exists in combination with the Renaissance palace. The original Ducal Palace is believed to have been built in the early ninth century, coinciding with the time that the Venetian Republic was developing as a world power. For this reason, Ruskin considers the modern day Ducal Palace to be one of the last remnants of the city’s former glory.The structure was heavily damaged by fire on two different occasions, and little is written about its original state, making it difficult to ascertain exactly how the building looked. However, Ruskin does say that the building was richly decorated with gold, sculpture, and marble, and possessed many features similar to those seen at other great Byzantine structures around the city, such as the Fondaco dei Turchi, built in the early thirteenth century by Giacomo Palmier.

Giacomo Palmier, Fondaco dei Turchi, early thirteenth century, Venice

The structure remained in the Byzantine style until the Gothic palace replaced it in the early fourteenth century. Ruskin points out that while the Byzantine palace coincided with the foundation of the Venetian Republic, the Gothic palace coincided with the beginning of aristocratic rule in Venice. The building was expanded to house the Great Council chamber, the Ducal apartments, and a series of rooms that served as prisons until the late eighteenth century. As one would imagine, he considers this stage of the palace’s construction the greatest, even calling the Gothic Ducal Palace “the Parthenon of Venice.”

However, during the fifteenth century, sections of the building were already being redone in the Renaissance style, beginning with the destruction of the last remnants of the Byzantine palace and the building of a new façade facing the Piazzetta (although this facade is no longer visible as it was rebuilt yet again under Doge Francesco Foscari to resemble the Sea Facade). The three facades represent the changes that occurred to the building, with the Sea Façade being the most Gothic and the Rio Façade being a prime example of early Renaissance architecture.

Antonio Rizzo, Pietro Lombardo and La Scarpagnino, Rio Facade of Ducal Palace, completed in 1559, Venice

Although Ruskin does not find the Renaissance elements at the Ducal Palace overly offensive, he does comment on their reflection of the changing religious environment in Venice at the time. He criticizes the shift away from sculptural scenes of Christ’s life, like those found at St. Mark’s, towards images of human virtues and literary references, noting that they changed “exactly in proportion as the Christian religion became less vital…and gradually, as the thoughts of men were withdrawn from their Redeemer, and fixed upon themselves,” yet another form of the self-indulgence that would contribute to the city’s fall.

This form of social commentary is prevalent throughout Ruskin’s work. While he is credited with spreading the popularity of Venetian architecture to the rest of Europe, he did not simply write The Stones of Venice to serve as an architectural guide to the city. But beyond his major influence on architecture and criticism, he is perhaps best known for the political and social undertones in his early work, despite their seeming focus on art and architecture. The majority of his work from the last thirty years of his life focused directly on politics and social history, making it seem, on the surface, as if he shifted gears in the middle of his career. However, this is certainly not true, he simply withdrew from using art as a means through which to communicate his ideas. In The Stones of Venice, Ruskin repeatedly raises questions about the relationship between art and society, and often relates the case of Venice to his native England, having written the book as an “awful warning to contemporary England.”The opening chapter of The Stones of Venice begins with a homily on the importance of learning from the history of previous fallen empires, with Tyre and Venice as his examples, concluding that if England forgets the example of their predecessors they may be subject to ruin of an equal or greater degree. This was not a particularly new idea at the time: Byron and others had touched on it earlier, but Ruskin was certainly the first to argue the point in such detail and with such intensity. He was also one of the first to develop fully the idea that a society’s morality could be discerned by studying their art and architecture. Despite his development of these ideas, his arguments often appear convoluted to the reader, resulting in the mediocre or confused receptions that he received from some of his contemporaries. For this reason, Ruskin considered The Stones of Venice to be a failure, for he was utterly disgusted that his third volume received the most attention while the earlier two were largely ignored when they were published, though they have since been thoroughly studied. Still, the work brought him much acclaim from those who were able both to press through to its end and understand what they had read, resulting in the enormous influence the book has had since its publication and marking the transition from his art-based criticism into political, economic, and social criticism.

Cornelis J. Baljon, “Interpreting Ruskin: The Argument of The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55, no. 4 (Fall 1997): 406, http://web.ebscohost. com (accessed September 14, 2008).

Deborah Howard, The Architectural History of Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 98.

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 7 of The Complete Works of John Ruskin(New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1905), 126.

Ibid., 139.

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 8 of The Complete Works of John RuskinNew York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1905), 248.

Ibid.

Ibid., 263.

Howard, The Architectural History of Venice, 98.

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 9 of The Complete Works of John RuskinNew York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1905), 16.

Ibid., 308.

Ibid., 3.

Ibid., 112.

Paulette Singley, “Devouring Architecture: Ruskin’s Insatiable Grotesque,”Assemblage, no. 32 (April 1997): 119, http://www.jstor.org (accessed September 27, 2008).

Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 9 of Works, 121.

John Lewis Bradley, 261.

Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Vol. 7 of Works, 17.

Ruskin, The Stone of Venices, Vol. 8 of Works, 287-288.

Ibid., 289.

Ibid., 291.

Ibid., 315.

Francis O’Gorman, “Ruskin’s Aesthetic Failure in The Stones of Venice,” Review of English Studies 55, no. 220 (June 2004): 374, http://services.oxfordjournals.org (accessed September 14, 2008).

Sarah Quill and Alan Windsor, Ruskin’s Venice: The Stones Revisited (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000), 19.

Ruskin, The Stones of Venice¸ Vol. 7 of Works, 1.

O’Gorman, 375.